Some love stories are born in silence.

Others are forged in blood, gasoline, and obsession.

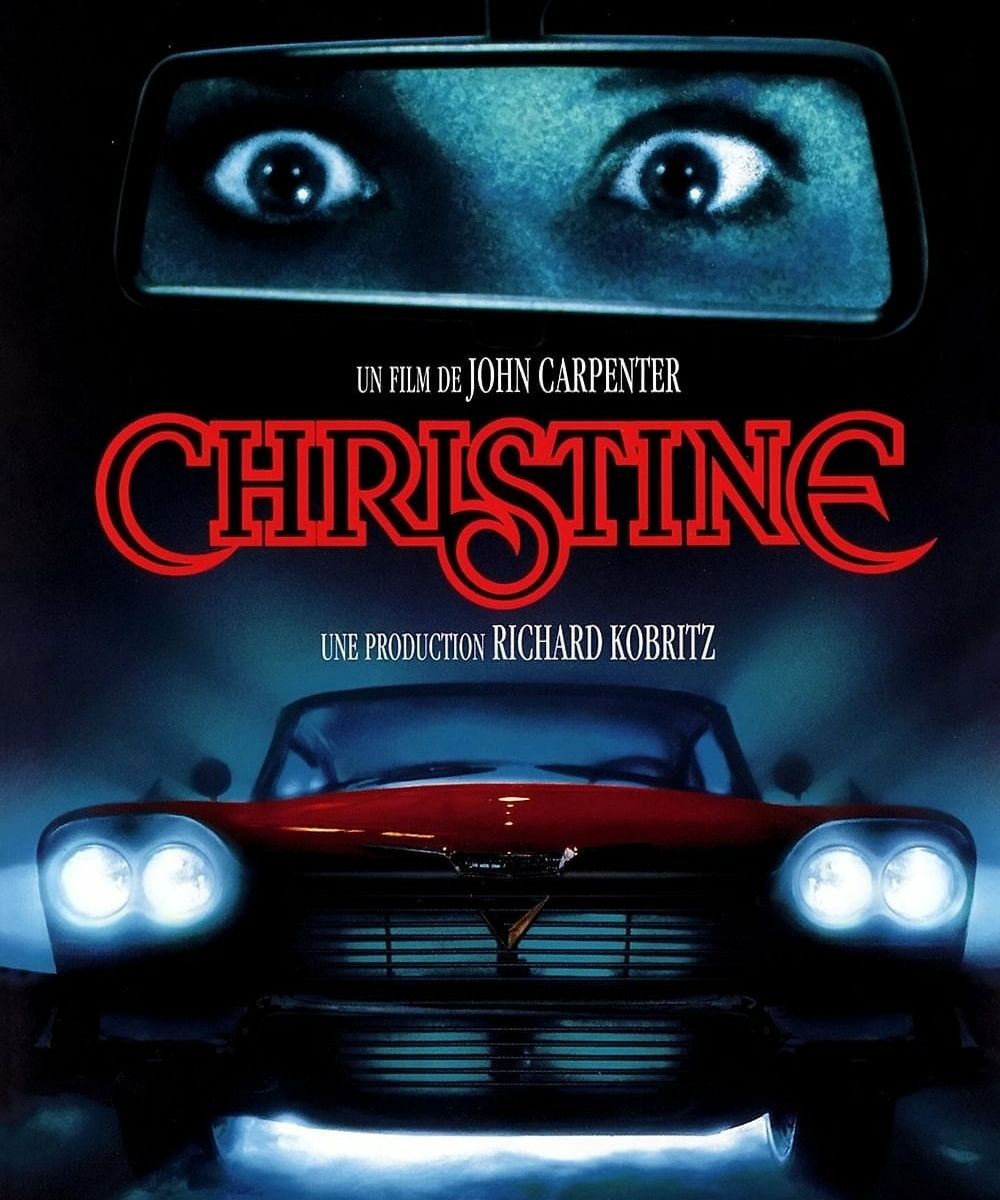

Christine (2026) is not simply a horror movie about a possessed car. It is a dark, seductive exploration of loneliness—of how the desire to be seen can turn devotion into destruction. In this reimagined cinematic vision, the story of Christine is sharpened for a modern audience while retaining the raw, emotional terror that made Stephen King’s original novel unforgettable.

The Birth of an Obsession

The film opens not with violence, but with isolation.

Arnie Cunningham is a quiet, awkward teenager living on the edges of his own life. At school, he is invisible. At home, he is suffocated by overprotective parents who mistake control for care. The world constantly reminds him that he is weak, forgettable, and easily replaced.

Then he sees her.

Christine.

A battered, rusted 1958 Plymouth Fury, abandoned on a sun-scorched street like a forgotten relic. Something about the car calls to him—not loudly, but insistently. The camera lingers on Christine’s cracked windshield, her faded red paint, as if she is watching him.

When Arnie buys the car against all reason, the audience already knows: this is not ownership.

This is recognition.

A Car That Understands Him

As Arnie begins restoring Christine, the film shifts tone. The garage becomes a sanctuary. Tools clang rhythmically like a heartbeat. Christine’s radio crackles to life, playing old rock-and-roll songs that feel strangely personal, as though the car understands Arnie’s emotional state.

Slowly, impossibly, Christine heals herself.

Dents disappear overnight. Rust vanishes. Scratches mend like skin. Each restoration mirrors Arnie’s own transformation—he stands straighter, speaks with more confidence, and begins to push back against those who once dismissed him.

But this empowerment comes at a cost.

Christine doesn’t just give Arnie strength. She feeds on him.

The Price of Devotion

As Arnie grows stronger, his relationships begin to decay.

His best friend, Dennis, notices the change first. Arnie’s laughter feels rehearsed. His eyes linger too long on Christine, as if listening to a voice no one else can hear. Christine, it seems, does not like competition.

Neither does she like rejection.

When a group of bullies vandalizes the car, the film delivers its first true act of horror. Christine hunts them—not as a machine, but as a predator. Headlights burn through darkness like eyes. The engine roars with hunger. Metal bends and reforms as she crushes her victims without mercy.

This is not revenge.

It is jealousy.

Love That Kills

The central theme of Christine (2026) is not fear—it is possession.

Christine doesn’t want to kill Arnie. She wants to keep him. To isolate him from friends, family, and the outside world until she becomes the only constant in his life.

The more Arnie gives in, the more Christine takes.

His girlfriend becomes a threat. His parents become enemies. Even Dennis becomes expendable. Christine frames each act of violence as protection, whispering through radio static and flickering headlights.

And Arnie believes her.

The Final Descent

By the final act, Christine is no longer hiding. She moves openly, confidently, unstoppable. The film embraces its gothic horror roots—firelight reflecting off polished chrome, shadows stretching across empty highways, rock music echoing like a funeral hymn.

Arnie realizes too late that Christine never loved him.

She only needed him.

The climax is tragic, brutal, and intimate. There is no grand victory—only loss. Christine burns, screams, and collapses in twisted metal, but her presence lingers even in destruction.

The final shot is hauntingly simple: a piece of chrome twitching in a scrapyard, as an old song crackles faintly through the air.

Christine is gone.

Or is she?